Sometimes, I feel like erosion is a big elephant in the room. It happens. It feels unlucky, it feels bad, and sometimes it feels inevitable. It is also still one of the biggest threats to long-term productivity and soil health that we face today, especially as the weather gets more erratic. Not talking about it isn’t going to make it go away. Soil erosion is not inevitable, nor is it just about luck. With certain management strategies, soil erosion can be dramatically reduced.

This happened as a result of my management. Sure it was years ago, but I still think about it.

I did this. I don’t remember specifics, but I think this was a field of tomatoes that came out in late fall then was tilled under, and there was no time (or so I thought) to establish a cover crop. After the winter snow melt and spring rains, this is what the field looked like. Tilling destroyed the soil’s aggregation, and leaving the soil bare left it susceptible to the forces of water. Just a little bit of slope (how many fields in the northeast are really flat, anyway?) was enough to wash a lot of soil away. I know I’m not alone in having created a situation like this.

Have we made enough progress?

Source: NRCS

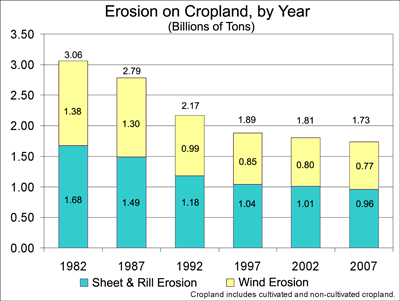

I think one reason people don’t talk about erosion as much as they used to is because, on a national scale, we’ve made tremendous progress in reducing soil erosion. Much of this is a result of no-till and conservation agriculture. But in the US, we’re still losing over 1.5 billion tons of soil to the forces of water and wind each year. And from my observations on vegetable farms, it seems like erosion is still common.

How much is too much erosion?

Losing a crop is a bummer. Losing the soil is tragic. This is too much erosion.

If you can see it, it’s too much. Soil naturally regenerates from the parent material (such as bedrock) at a very, very slow rate, but “sustainable” soil loss estimates are generally in the range of 2-5 tons of soil per acre per year. This may sound like a lot, but that’s less than half a dime’s thickness. If the soil loss is perceptible to your naked eye, it’s too much. Ten inches of topsoil quickly becomes nine inches of topsoil, and so on. Many fields today “suffer” from the erosion losses from centuries past.

More water, faster, requires good infiltration

A soil crust prevents water from infiltrating, which is especially bad in big rain events.

Intense storm events can drop water faster than the soil can absorb it, sometimes leading to tons of soil loss over a short period of time. This is exacerbated by poor soil health conditions, like low organic matter and poor soil aggregation that can cause crusting (right) and low infiltration rates. Even if the soil doesn’t leave the field, movement of soil within a field can also lead to trouble (below).

A poorly aggregated silt loam soil after a major rain storm on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Photo credit: Natalie Lounsbury

Unfortunately, data clearly indicate that we are having more storms of high intensity than occurred in the past. I’ve dubbed this “weather erraticization,” though I don’t think the term has caught on yet. Our generation has to think about adapting soil management practices to these events even more than previous generations. We have better knowledge and technology to prevent erosion than previous generations, however, so don’t stop reading yet!

Strategies to minimize erosion with cover crops

Increasing a soil’s resistance to erosion and decreasing the amount of time a soil is left susceptible to erosion are the best ways to keep soil in the field. A soil is resistant to erosion if it has good aggregate stability and a high infiltration rate (low compaction and lots of biopores for water to flow). A soil is less susceptible to erosion of it has living plant roots (and lots of them) and is covered (mulched).

On this sloped land, forage radish did not prevent “unsustainable” levels of soil erosion after it winterkilled (note the gulley).

Cover crops are key to all of these functions. Grass cover crops with fibrous root systems can increase a soil’s aggregate stability while also covering and protecting the soil. Cover crops like forage radish can increase infiltration rates through biodrilling. Forage radish is not, however, the best cover crop for preventing erosion (left), and may be best in a mixture on sloped land. All cover crops provide food for the soil food web, and ecosystem engineers like earth worms, which aggregate the soil and create biopores.

The question then comes down to how to grow more cover crops and minimize the time soil is left susceptible to erosion while also growing cash crops. Let’s go back to the field I first showed of the soil I tilled in late fall and left bare over the winter.

Just another picture of this field.

What if I had done something like this, instead:

The Penn State interseeder seeds cover crops into standing corn so they have longer growth window in fall.

This is a spring photo of the plots from the Penn State Interseeder trial. This system is based on corn, not vegetables, but the same concepts can apply. Earlier seeding into standing corn gives the cover crops a longer growth window, thus enabling them to do more good, while not competing with the cash crop too much.

A crimson clover and phacelia cover crop between rows of Brussels sprouts.

On a small scale, I’ve done similar things using an Earthway push seeder to seed the pathways of late season brassicas. It should be noted, however, that some research has shown that certain living mulches in the pathways may reduce yields of broccoli grown in plastic. I did not do a full experiment and collect yield data on the Brussels sprouts (below), but given the erodibility of this field, I felt confident about my choice to use a cover crop/living mulch in the paths.

Moving toward less soil disturbance

There’s a lot I haven’t discussed here related to reduced tillage and other management techniques that can minimize soil disturbance and reduce erosion potential. I also haven’t discussed a different kind of erosion caused by tillage itself, called (surprise) tillage erosion. I’m working away at my new project, a podcast on soil health, where I’ll talk about more of these things. In the mean time, as I’ve been driving around and seeing bare fields with little gullies running through them, I’ve had erosion on my mind and I wanted to write about it.

p.s. when you look for soil loss, you really do start to see it everywhere. After writing this post, I saw this yesterday not far from my house in Maine. It was windy and this soil was blowing far away from the field. I’m not sure if this would be considered wind erosion or tillage erosion or some combination of both, but goodbye, soil.